Facility-rich and cash-poor, the Oregon Ducks need your donations

Phil Knight’s financing plan for Oregon’s Best-in-class Arena put the Athletic Department in a huge financial hole. AD Rob Mullens needs your donations to dig out the Ducks.

Key Takeaways:

Phil Knight’s financing plan for Oregon’s Best-in-class Arena put the Athletic Department in a huge financial hole.

Oregon’s AD predicted the Arena would break even in 2013. It lost $11.5 million in 2013 (and continues to hemorrhage cash today).

Past media revenue windfalls saved the Ducks from massive budget cuts.

Oregon needs the Big 10’s future media revenue to stay afloat.

Knight was likely silent on Oregon’s departure to the Big 10 because it was in part his Legacy Fund plan that drove the Ducks to blow up the Pac-12.

AD Rob Mullens’ recent fundraising plea reflects the new reality for the Ducks. The football program needs to balance raising cash for player payrolls, while still needing donations to meet massive debt obligations and take care of expensive-to-maintain buildings.

Build It and They Will Come

Oregon spent nearly $700 million on new athletic buildings over the past sixteen years, primarily funded by Phil Knight’s conditional generosity (Table 1). This spree increased Oregon’s annual building expenses from $5.4 million to $39.8 and ended just as cash replaced facilities as the currency of player recruitment. Now, these world-class facilities host all kinds of money-draining sports; track and field, baseball, softball, soccer, and the biggest drain of all, men’s basketball.

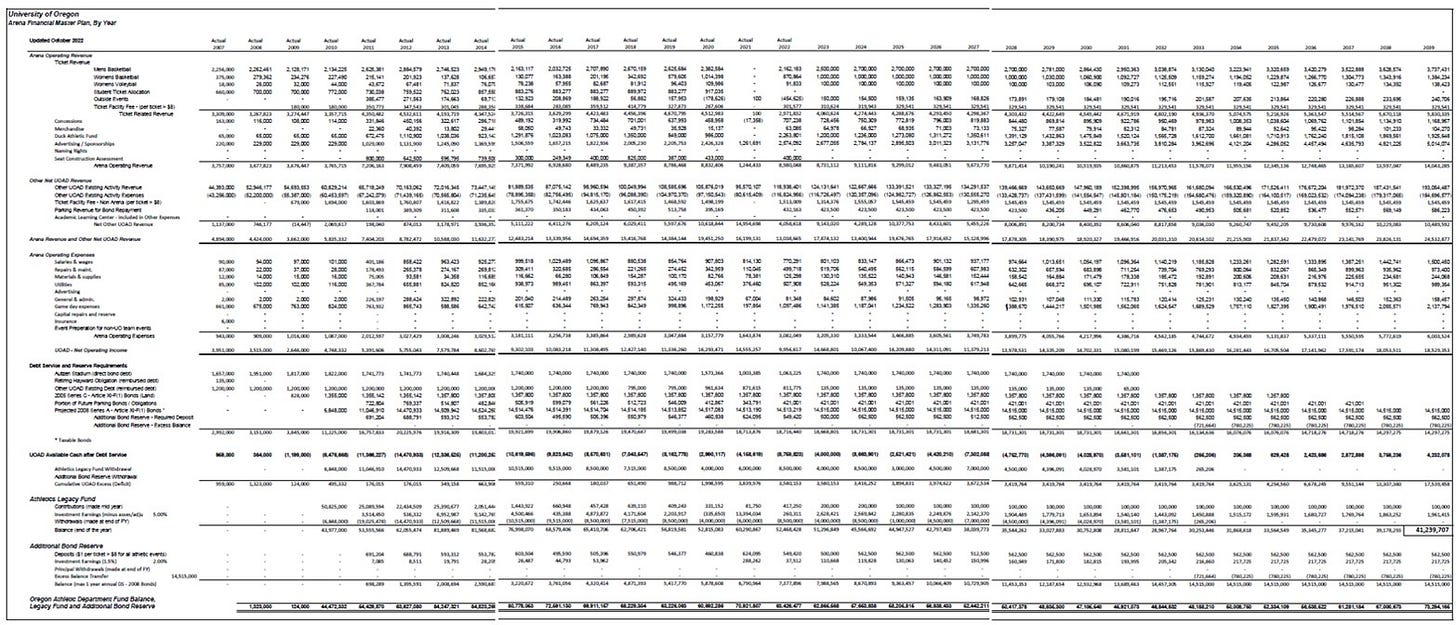

Yes, men’s basketball is the biggest drain of all, and its place at the top of the money-losing list can be attributed in part to a failed Arena financing scheme pushed by Nike’s owner. Our window into how Knight’s scheme unfolded into a huge cash drain are coffee-table-sized spreadsheets published annually 1 by the Athletic Department (Figure 1). You can find the full series of these spreadsheets here. The spreadsheets track the status of the “Legacy Fund,” the linchpin of Knight’s failed scheme. The billionaire established the fund in 2007 to great fanfare with a pledge of $100 million. At the time, UO president Dave Frohnmayer claimed the gift would “set the university’s athletics on a course toward self-sufficiency and create the flexibility and financial capacity for UO to build a new athletic arena.”2 Since then the fund has been relegated to a shell game of sorts, continually hiding financial missteps and unfunded promises.3

Knight’s Grand Arena Plan

Planning for a new arena to replace the historic Mac Court started in 2002 with a survey of potential sites conducted by Convention, Sports, and Leisure, Inc. (CSL). This was followed by preliminary plans for a new arena in the $60-$80 million range. In 2005 Knight’s preferred site for the new arena came on the market with a steep price tag ($22 million). He then pushed for a $200 million arena budget. Together, the cost of land and building would result in the most expensive college arena ever built (and on par with NBA and NHL arenas). Knight, who could write a check for the full amount, instead pledged $100 million to the quasi-endowment/Legacy Fund, on the strict condition the State of Oregon guaranteed a $226 million bond issue for the full cost of the new arena.

Knight’s plan to build an NBA-worthy arena and underwrite the long-term success of the Athletic Department had five components; 1) seed his “Legacy Fund” with a $100 million donation, 2) attract an additional $50 million from other donors, 3) convince state legislators that the Arena would be self-sufficient and never draw on the Legacy Fund, 4) close the deal with the state legislators to issue and guarantee bonds for the full amount of the Arena project, and 5) invest his Legacy Fund cash balances aggressively (8% to 10% returns) to beat the interest rates charged on the State-backed arena bonds (3.5% to 4.5%) to generate extra income for the Athletic Department.

Knight’s plan was met with extreme skepticism by university faculty and officials outside the Athletic Department. His plan veered dramatically from traditional financing plans where an equal share of cash donations and university-backed bonds paid for new buildings. It was also unusual to ask a state government to back a bond for a university arena or stadium, and for that bond to be underwritten in part by an arbitrage scheme (profiting on the spread between borrowing costs and investment returns).

Plenty of Red Flags

Knight’s arena plan was evaluated by a faculty committee composed of experts in economics, sports management, and public finance. A sentiment guiding their deliberations was that:

“the sheer scale of this [Arena] investment challenges the perception that the University is focused on academic excellence as its top priority.”

The committee’s findings were published in a 2008 report to the Faculty Senate and University president.4 The report raised issues with the cost of the project, aggressive internal revenue estimates, and the complexity of the financing plan.

The committee noted that the Athletic Department’s consultant (CSL), surveyed 43 new collegiate basketball arenas and found that the average cost of a new arena was $65 million. The CSL survey also found no university used 100% bond financing for a new arena. The biggest share of bond financing (versus donor funding) for a new arena was 50% by Ohio State University. Many of the arenas in the CSL survey carried no debt payments as they were funded 100% by donations.

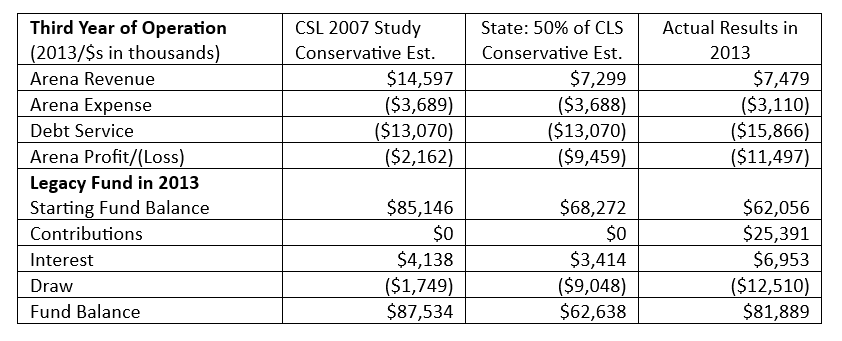

CSL also published revenue and expense estimates for the proposed arena, although much of the revenue component was based on estimates from Athletic Department staff. Speaking to the Oregonian newspaper in the Fall of 2007, UO Athletic Director Pat Kilkenny declared strong support for staff estimates that ticket sales and other arena income would generate $16 million per year.5 The faculty committee challenged the methodology behind staff estimates, noting that they were “not subject to any market test or certification until CSL conducted its market research in 2007.” After CSL completed an online survey of potential ticket purchasers, the firm provided a conservative estimate that the Arena would generate $14.6 million in revenue in the third year of operations.

Despite the AD’s enthusiasm and CSL’s survey results, committee members treated CSL’s conservative estimate as optimistic, writing in its evaluation. “Any prudent assessment of the revenue-generating capabilities of the proposed arena will treat the CSL 2007 Conservative estimates as an upper limit of what Duck fans are willing to pay for admission to men’s basketball games.” The committee suggested that using 50% of CSL’s conservative estimate ($7.3 million in revenue per year) was reasonable for planning purposes.

As for the financing plan offered by Knight, the committee questioned the legality of using arbitrage as a source of income. The IRS prohibits this practice for tax-exempt borrowings, but the university’s legal staff argued that interest earnings from the Legacy Fund would never be used to make any portion of the debt payments.6 This issue became moot later in the process as Oregon opted to issue less restrictive (and much more expensive) taxable bonds to avoid the arbitrage issue.

The committee concluded its assessment of the Arena financing plan by estimating that the Legacy Fund, using 50% of CSL’s conservative revenue estimates, would be drawn down to a zero balance in 2024. With that scenario in mind, here is a partial list of the management recommendations offered to the university president and Athletic Department by the committee:

The Athletic Department should issue regular financial statements for the Arena and detail any use of department revenue or Legacy Fund balances to cover revenue shortfalls.

The Athletic Department should invest Legacy Fund balances conservatively until the fund balance exceeds $75 million and arena operating income exceeds CSL’s conservative estimates.

Any necessary budget cutbacks due to revenue shortfalls should be borne by the Athletic Department.

The Athletic Department should limit the expansion of facilities and programs until the arena is profitable.

With the Athletic Department benefiting financially from using the State of Oregon’s credit rating, a portion (5%) of any excess arena revenues should accrue to the university for academic purposes.

Knight’s Folly

The Arena opened in 2011, financed 100% with State of Oregon-backed taxable bonds, and immediately lost $11.5 million in its first year. Seeing the financial disaster on the horizon, AD Rob Mullens issued an operational assessment three months before the Arena opened. His assessment concluded that the original intent of the Legacy Fund was seriously compromised by lackluster ticket and sponsorship sales, writing “The Athletic Department clearly faces some significant financial challenges” and that “careful fiscal management” was needed to turn around the department’s fortunes.7

The financial challenges Mullens’ referenced were tied directly to Knight’s financing scheme. Table 2 below compares two projections of the Arena’s stabilized performance (2013/year 3) versus the actual performance. CSL’s projection of Arena revenue in 2013, strongly backed by the Athletic Department, was nearly twice the amount of the actual revenue taken in that year. Debt payments, already high due to financing 100% of the Arena cost, increased another 20% as a result of shifting to a taxable bond to avoid issues with IRS arbitrage regulations. Finally, the draw against the Legacy Fund in 2013 was nearly $11 million greater than originally projected. The fund balance of the Legacy Fund was propped up in 2013 by an unexpected one-time donation and the carryover of interest revenue from 2012.

Despite the Athletic Department’s 2010 call for “careful fiscal management,” the Arena has not come close to approaching the financial performance predicted by CSL and Athletic Department staff. After predicting the Legacy Fund would never be used to pay bond payments, it has done so in twelve of the past fourteen years. When the 30-year financing for the Arena is finally paid off, the total payments under Knight’s plan will reach nearly $480 million. If the university had chosen a traditional path, convinced Knight to apply his $100 million donation towards construction, and borrowed the balance using tax-exempt bonds, the payments would have totaled just $211 million, a savings of $266 million.

Saved by Media Deals

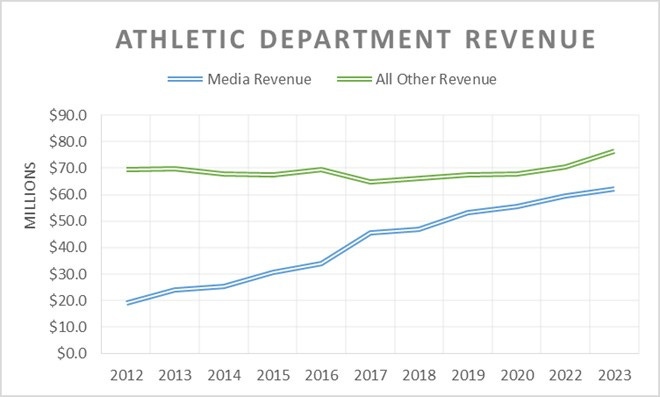

At the time the Knight Arena was financed, the Athletic Department projected a 2.5% annual increase in department revenues over the life of the arena bond debt (through 2038). With that projected level of growth, the Legacy Fund would have been exhausted this year (2024). Fortunately for the Ducks, there was an unforeseen explosion in media revenue that all major conferences enjoyed over the following 14 years. This unexpected growth is the only reason Oregon survived Knight’s failed Arena financing plan. While all other revenues in the Athletic Department budget increased at an annual rate of 1.5% over the past 14 years, media revenue increased at an annual rate of 13% (Figure 2). Oregon took in $19 million in media-related revenue in 2012 and by 2023 that number increased to $62 million. During the same period, non-media revenue in the Athletic Department only increased from $69 million in 2012 to $76 million in 2023.8

A few additional benefits of the media revenue windfall for the Athletic Department are that discussion about sharing a fraction of surplus revenue from the Arena with the academic side of the university never resurfaced, and no one questions why Knight was given the valuable naming rights for the arena when it is hemorrhaging cash under his failed financing scheme.

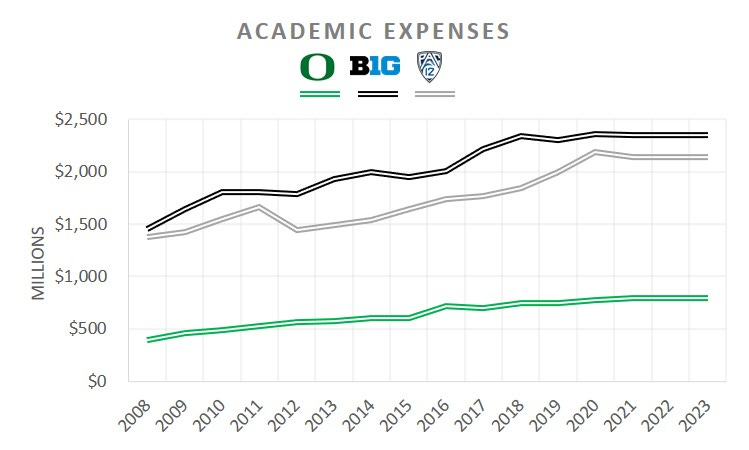

The Ducks Need Help in the Post-House Era

The Ducks' lavish facilities and ties to Nike were very attractive to student-athletes before they were paid for their services. Great facilities and Nike may still be a factor, but direct compensation is expected to trump facilities in post-House recruitment battles. Oregon is now saddled with expensive-to-maintain facilities, a Legacy Fund with limited value due to the Arena financing fiasco, a donor base likely to target donations at player payrolls (and the chance to rub elbow with potential superstars), a relatively small academic budget upon which to bail out the athletic department (Figures 3 and 4), and limited prospects for the State of Oregon to boost the school’s funding to address facility maintenance.

Oregon AD Rob Mullen’s recent plea for donations from the masses reflects a grim reality. The Ducks are long on expensive-to-maintain, somewhat irrelevant buildings and short on cash for player payrolls. They desperately need a Legacy Fund II – one without strings attached from its biggest donor.

Footnotes

Oregon originally published these to appease faculty members concerned about the magnitude of the debt the Ducks took on with the Arena.

University of Oregon Receives $100 Million for Athletic Programs, Philanthropy News Digest, August 22, 2007

One expense of the Athletic Department that disappeared when the Arena revenue nosedived was the operating cost of the academic center donated by Knight and restricted to student-athletes only. In the original Legacy Plan, the Athletic Department was to fund the center’s staffing. That expense disappeared in subsequent Legacy Fund updates. Through 2024 that missing line item shifted potentially $6.6 million in costs to the university. See “Oregon Athletic Department Uses State Money for Academic Needs,” Oregonian, October 7, 2010

UO Senate Budget Subcommittee on Arena Financing, Final Report, January 9, 2008.

Summary: The school says it will repay the $200 million with revenue from the facility and fan donations. Oregonian, October 9, 2007,

Legality of new arena’s finances questioned, Daily Emerald, October 31, 2007

Operational Assessment, Memorandum from Athletic Director, Rob Mullens, September 28, 2010.

Revenue estimates were retrieved in November 2024 from the Knight-Newhouse College Athletic Database. https://knightnewhousedata.org/

Typical billionaire financing scheme: use as little of their own money as possible and rely on public and other people's money to get their palaces built; make preposterous projections of revenue, in line with their inflated ego; and sit back and enjoy the spoils while leaving others to clean up and pay for the mess.

Bill, when you say "academic budget" this includes research grants, correct? The results in Fig 2 and 3 then reflect that U Oregon ranks 147th in ranking of R&D expenditures (NSF NCES), far below (often $1B below) many of their Pac12/B1G compatriots. UO isn't helped by fact that biomedical research done at OHSU, whereas many other R1's have a lucrative med school (e.g., U Washington). Thanks for this!