Private Capital Stings the University of South Florida on Stadium Financing

Using FSU's recent public bond issue for comparison, I estimate USF's choice of private capital over traditional public financing caused a $100 million bust in its new stadium cash flow projections.

Florida state statutes exempt certain affiliates of university athletic departments from public records requests (section 1004.28). Therefore this analysis relies on records within the public domain and some reasoned speculation to address gaps in that record.

EDITED 6/19/24: Added warning letters from the Division of Bond Finance

Introduction

While writing about the potential for private equity investment in the Florida State University Athletic Program, I caught a few articles on the University of South Florida’s stadium construction process. I noted the cost of building USF’s new stadium ($340 million) was close to the cost of renovating FSU’s stadium ($284 million), yet during my research on FSU’s renovation project I did not recall seeing any record of bond financing for USF’s stadium. With a little research, I discovered that USF used private capital to finance its stadium - setting up a nice comparison between FSU’s traditional public finance approach, and USF’s trendy venture with private capital.

Florida State’s bond financing closed last week. Scanning the various purchasers of those bonds it appears the equivalent interest rate for the borrowing will be about 4.5%. This can be contrasted with USF’s private loan rate of 6.48%. USF closed on that private bank loan in December 2023 to finance $200 million of its new $340 million stadium.

I reviewed the public record to see if I could find out why USF came to the unusual decision to use private capital for such a large project ($340 million). What I found is a story unto itself. USF’s Stadium Feasibility Study assumed the use of low-cost public financing, but during the project planning phase, USF staff elected to pursue a private bank loan. At first, USF staff explained the decision to their Board of Trustees that lower fees associated with obtaining a private loan would allow more money to go into the stadium construction project. Later USF staff changed its story to indicate the stadium project borrowing, which was to rely solely on stadium revenue, was too risky to take into the public bond market.

Neither story makes sense.

In this article, I take you through a timeline of the planning for USF’s stadium and the documents decision-makers reviewed to substantially increase the cost of financing for its new stadium.

USF’s Dream of a New Football Stadium (2018-2021)

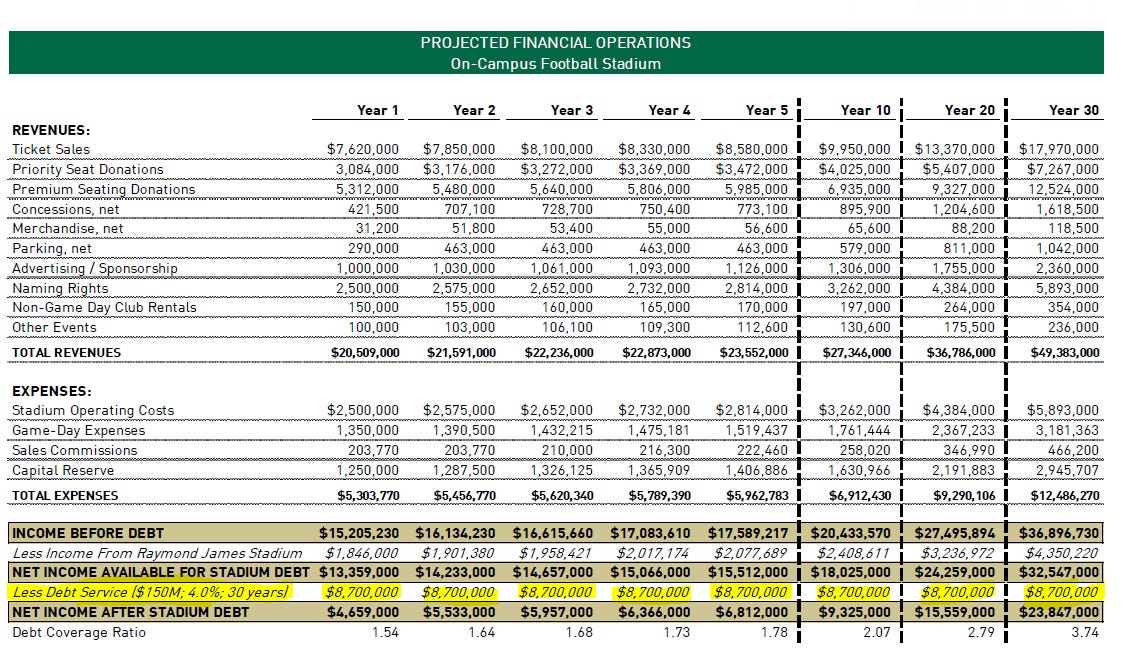

USF retained Conventions, Sports & Leisure International (CSL) in 2018 to conduct a stadium feasibility study and again in 2021 to update the initial study. CSL recommended a building program of 35,000 seats (Figure 1) with a price tag of $303 million. CSL also suggested a financing plan that consisted of $153 million in cash and $150 million in public bond financing ($8.7 million per year) (Figure 2).

Private Capital Enters the Chat (2022-2023)

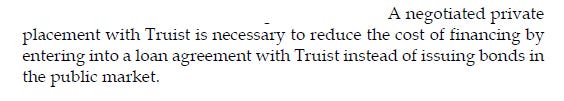

USF adopted the building program and cost estimate recommended by CSL but opted to use private financing for the debt portion of the project. USF cited the excessive administrative costs for preparing and selling public bonds (Figure 3). This is a valid issue for small borrowings, as the costs can reach $500,000 for preparing detailed official statements and $500,000 to $1.0 million for commissions to sell the bonds to investors.

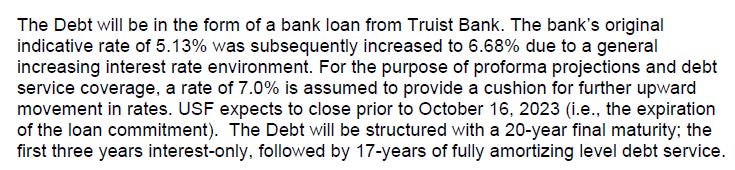

USF issued an Invitation to Negotiate (ITN) in June 2022 to eight private lenders for the “Direct Purchase of Taxable Revenue Bonds.” The ITN specified the need for a “$100-200 million fixed-rate, 30-year, taxable, privately-placed loan” that was “non-recourse financing to the University’s credit.” Three proposals were received and Truist Bank was selected as the preferred vendor for issuance of “Non-Bank Qualified Taxable Revenue Bonds” with an initial interest rate proposal of 5.31% (the length/term and collateral were not disclosed publicly).

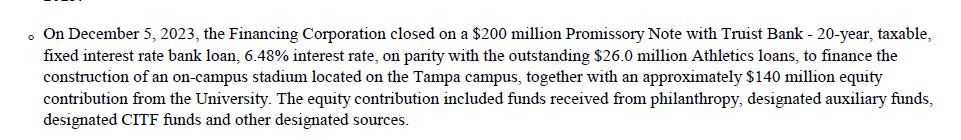

Fast forward to June and September 2023 and the terms of the Truist bonds are presented first to the USF Board of Trustees (June) and then to the Florida State Board of Governors (September). The recommended terms with Truist were $200 million with a 20-year term at an interest rate of 6.68% (Figure 4). The first three years during construction of the stadium are interest-only payments, and the payment after construction is estimated at $17.7 million per year (versus CSL’s pro forma at $8.7 million).

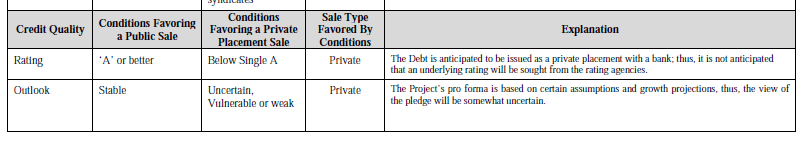

When the terms of the Truist private bonds/loan were presented to the USF BOT, revealing a $9.0 million increase in debt payments over those projected by CSL, USF changed the explanation for using a private lender. USF changed the rationale from A) savings on loan documentation and brokerage fees (Figure 3 above), to B) the “characteristics of the proposed USF Stadium Project (Figure 5).” USF presented its Board of Trustees with several aspects of the project that favored the use of a private bond/loan - most importantly the poor credit quality of the project’s repayment sources (stadium revenue growth projections)(Figure 6).

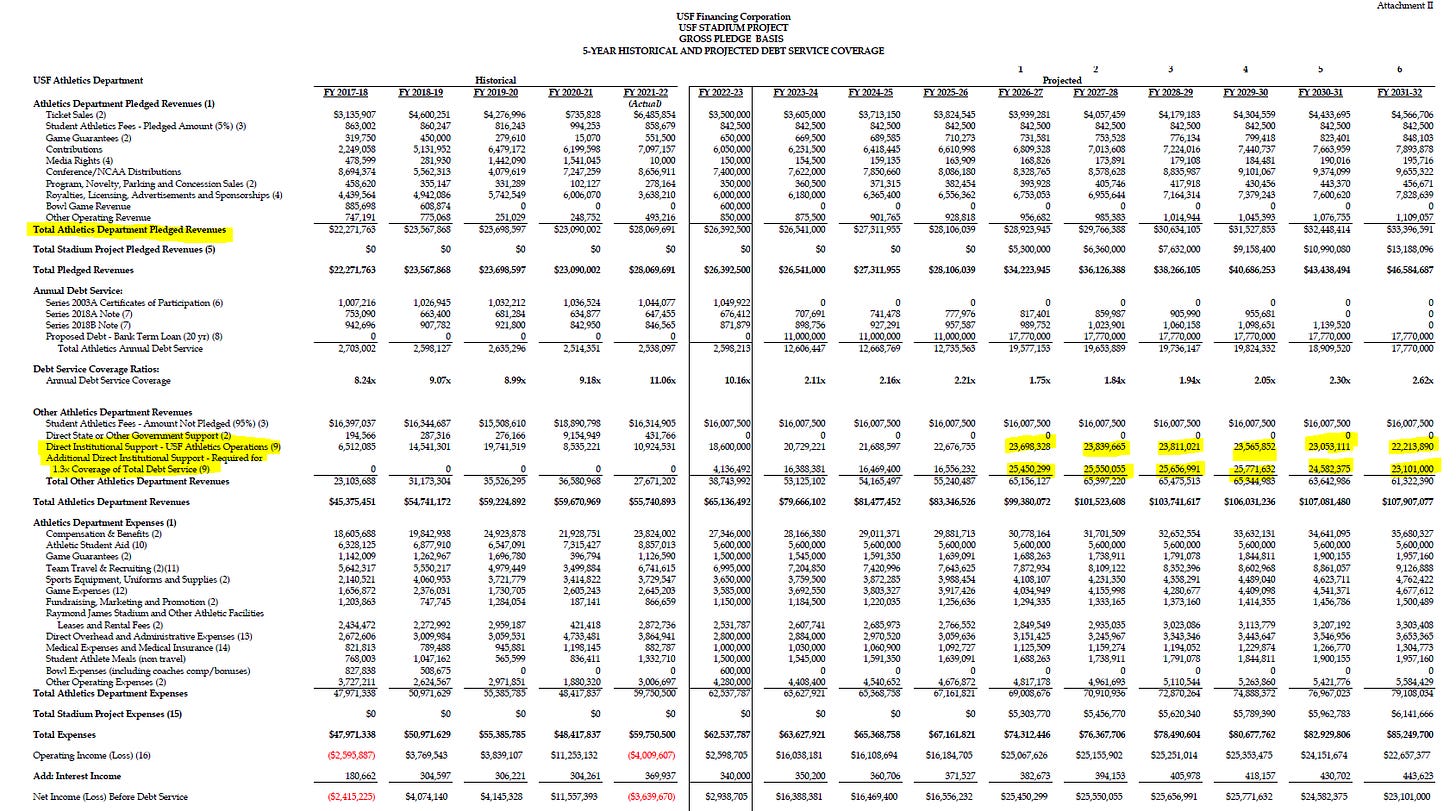

The poor quality of the repayment stream is contradicted by the financial projections of the project, as the too-large-to-read spreadsheet (Figure 7) included line items for 1) the Athletic Department to use non-stadium revenues to repay the stadium loan, and 2) USF’s pledge of “Direct Institutional Support” and “Additional Direct Institutional Support” to guarantee the payment of the loan/bonds. Use of all Athletic Department revenue and direct institutional support almost assures that the rating of a public bond for the stadium would be “A” or better and result in an interest rate similar to what Florida State received (in the 4% to 5% range).

USF ended up closing the loan in December 2023 at a slightly lower interest rate of 6.48%, but a higher annual payment of $19.6 million a year (versus $8.7 million per year in CSL’s pro forma which used public financing)(Figure 8). The jump in payments appears to be due to an error in the amortization table presented to the USF Board of Trustees and the Florida State Board of Governors in June and September 2023.

One Final Financial Note (Primarily for Financial Geeks)

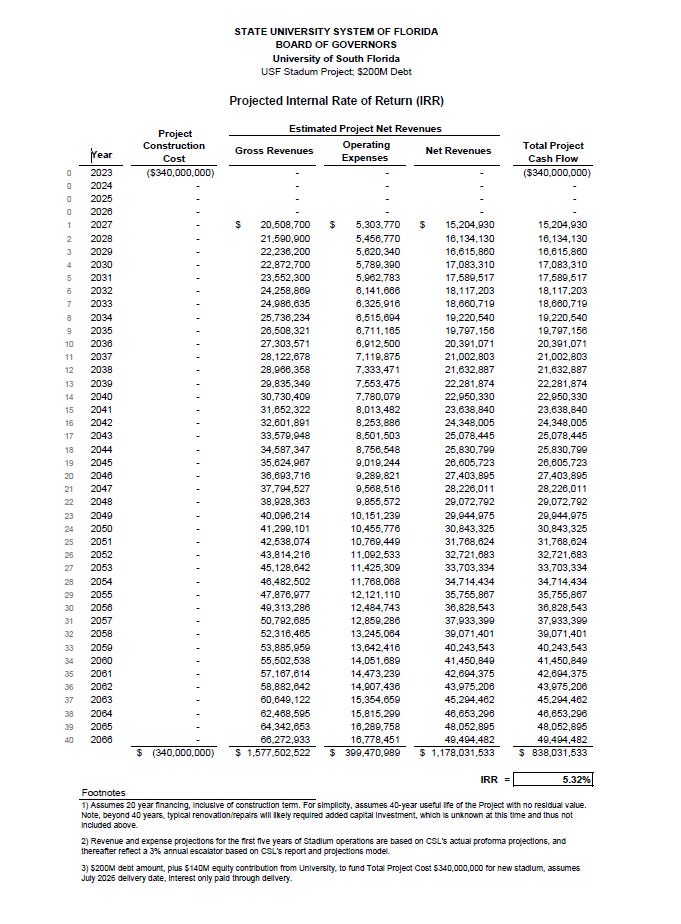

One of the staff exhibits presented to the State of Florida Board of Governors was a Projected Internal Rate of Return for the stadium project. USF represented that the project will generate an unleveraged (no debt) 5.32% rate of return over forty years (Figure 9). The problem with this representation is that it does not factor in the high cost of financing, which at 6.48%, depresses the IRR. Think of it this way, if you have an all-cash investment that produces a 5.32% return, would you replace your cash in that investment with a loan at 6.48%? With the layering of the loan into the analysis, the leveraged (with debt) IRR for the project drops to 1.94%. In my opinion, the leveraged IRR should have been presented to the Board of Governors.

Why did USF Fall for Private Financing?

In the absence of any compelling reason for USF to ignore its consultant’s financial plan and choose to use high-interest rate private financing, the choice of Truist Bank may lie with personal banking relationships and trust between USF staff and the bank. These relationships navigated around at least two guard rails the State and USF put in place to avoid such an occurrence.

State regulations (1010.62) regarding taxable revenue bonds require that they be analyzed by the Division of Bond Finance and [that] issues raised by such analysis” be appropriately considered by the Board of Governors.

There is no record I could find of this happening.The Division of Bond Finance provided the Board of Governors with two detailed memos outlining significant issues with taxable financing and no consideration was given to those concerns (Letter attached).USF’s policy on debt is that “The University will not approve any financing proposal which the University believes in its sole discretion will result in the selected Private Entity’s financing being considered indirect debt of the University by any national rating agency currently rating University debt.” Yet, the University clearly shows in its financial forecasts that the university is on the hook for any shortfalls - rating agencies will certainly consider this an obligation of the university which impacts its credit rating (Figure 7).

The power of personal relationships is evident in the decision-making process at USF to choose a local vendor to provide private capital over working with a state agency in another city on a public bond issue. This was an expensive decision that certainly will be repeated elsewhere in the country.